An Isolated Case or a Representative of a New Age for Independence Movements?

By Max Druckman

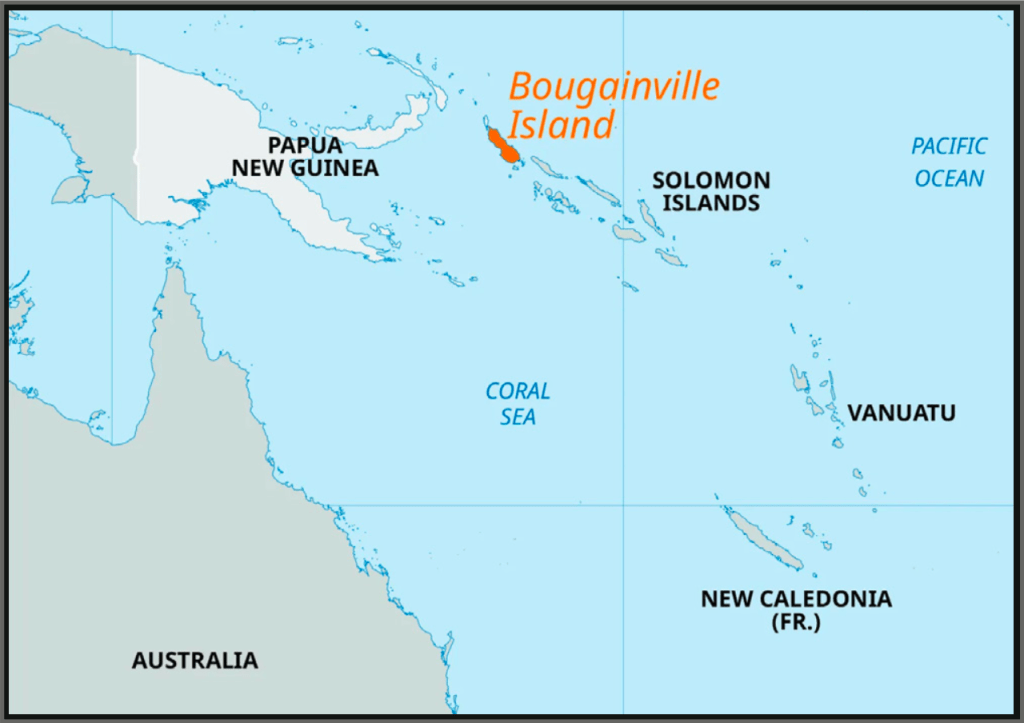

Historically, nations vying for independence have made international headlines and, sometimes, prompted international conflict. Yet, the international community’s next addition could be an obscure island in the South Pacific Ocean called Bougainville Island. The third largest of the Solomon Islands Archipelago, it is an Autonomous Region of Papua New Guinea. However, its foggy path toward independence encapsulates a shift towards an era of fewer newly independent nations.

Bougainville’s Story

In December 2019, Bougainville voted for independence, with 98 percent of voters backing the measure in a referendum. The referendum represented a culmination of the 1988-1998 war between Papua New Guinea’s army and Bougainville’s rebels that claimed 20,000 lives. The violence was prompted by the operation of a lucrative copper mine by the federal government and the Rio Tinto Corporation. The government, not Bougainville, reaped the profits, prompting residents to detest that the pollution and disruption yielded no rewards.

Five years later, Papua New Guinea’s parliament has not ratified the referendum. Parliament seeks a two-thirds majority for ratification, while Bougainville favors a simple majority, with both sides calling for international moderators to bridge the divide. Pouncing on the turmoil, foreign powers have grown interested in the conflict. Ishmael Toroama, Bougainville’s president, has been lobbying the US to invest in the Panguna mine, the same mine that previously sparked conflict. Funding the mine could prompt Bougainville’s self-sustainability and make it an American ally. Simultaneously, China has instituted trade relationships with Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, appearing poised to target Bougainville next.

Independent Nations: A Disappearing Trend

Bougainville’s slow path toward independence represents a trend within the international community. Since 2002, just two newly independent nations have ascended to the United Nations.

South Sudan seceded from Sudan on July 9th, 2011, and joined the UN five days later. Like Bougainville, its independence push resulted from a civil war. In 1983, Sudanese President Nimeiri imposed Shari’a law nationwide and revoked the South’s autonomous status. The subsequent civil war lasted until 2005 and killed 2.5 million. The tragedy’s scale and high-profile caused South Sudan’s independence effort to become recognized globally, unlike Bougainville’s cause.

Montenegro is the second most recent nation to gain recognition. Following the Balkan wars of the 1990s, Montenegro emerged independently in tandem with Serbia. On May 21, 2006, Montenegro’s citizens voted for independence, and, by July 27th, it joined the UN. Like South Sudan, Montenegro’s history of conflict and independence journey was more ubiquitous in the international community’s consciousness than Bougainville’s. Thus, both South Sudan and Montenegro utilized their widely-known conflicts and comparative historical prominence as springboards for rapid recognition. The ease with which their independence was garnered, though, appears to be a bygone artifact.

Struggling Modern Independence Movements

Like Bougainville, many active separatist movements have been unsuccessful. Catalonia voted in 2014 to separate from Spain, and again in 2017 with around 90 percent of the vote, though Spain considered both referendums illegal. Catalonia has held autonomous status since 1978 and feels that its productive economy is being exploited by the federal government, similar to the Panguna mine in Bougainville. Pro-independence protests have persisted since 2017, and Catalonian political leaders have been arrested and charged with treason. Both Catalonia and Bougainville are economically lucrative and historically autonomous. Nonetheless, both have seen their independence referendums neglected by central governments, with most of the international community remaining silent.

Further, the French territory of New Caledonia’s separatist movement is comparable to Bougainville. The indigenous Kanak people comprise 40 percent of the region’s population but control the government, desiring independence by 2025. The island saw civil war during the 1980s and three independence referendums have failed since 2018. In 2024, a state of emergency was declared following five deaths during independence protests. Both Bougainville and New Caledonia have been rendered geopolitical afterthoughts by most of the international community. Despite clear yearnings for independence, division remains the only realized outcome.

The Future of Independent Nations

The difficulty Bougainville, as well as Catalonia and New Caledonia, have faced in gaining independence initiates a larger question of why newly independent nations are a 21st-century rarity. One rationale is that most land has already become independent nations. Unlike the 20th century’s latter half, when most new countries were colonies of European powers, most modern independence movements occur in breakaway states. Global powers and multilateral institutions tend to condemn breakaway states as a threat to the post-colonial world’s stability. Also, with powers like the US and China catering to smaller nations for economic and political interests, the wider world may seek to prevent new independent nations to hinder the reignition of a Cold War.

The two most recent independent nations, Montenegro and South Sudan, emerged from widely-known conflicts with immense destruction. They were the last relics of the 20th-century era of expansion, as their root conflicts lay in either colonialism (South Sudan) or the Cold War (Montenegro). However, today’s international community is not eager to welcome new members and views separatist movements unkindly. As Bougainville proves, faraway independence movements are not an urgent task for most of the international community, a mindset even a Civil War has not been able to alter. Thus, for Bougainville, Catalonia, and New Caledonia, an independent future looks to be a relic of the past.

This piece is a reproduction from its original issue in Hemispheres Volume 48 Issue 1. Read more here.