By Jake Lanier

In recent years, wars have broken out across the world, dominating the news. It is as if one cannot go a day without confronting the political, humanitarian, and economic fallout of wars like those in Ukraine or the Middle East.

But what of their consequences for our planet? Although ecological damage is an often overlooked consequence of warfare, it is often among the deadliest elements of a conflict. World leaders rarely consider the environmental impacts of their foreign policy, yet at a time when climate change, population growth, and ever-increasing extractive activity already burdens our ecosystems, these consequences can no longer be ignored.

Ukraine

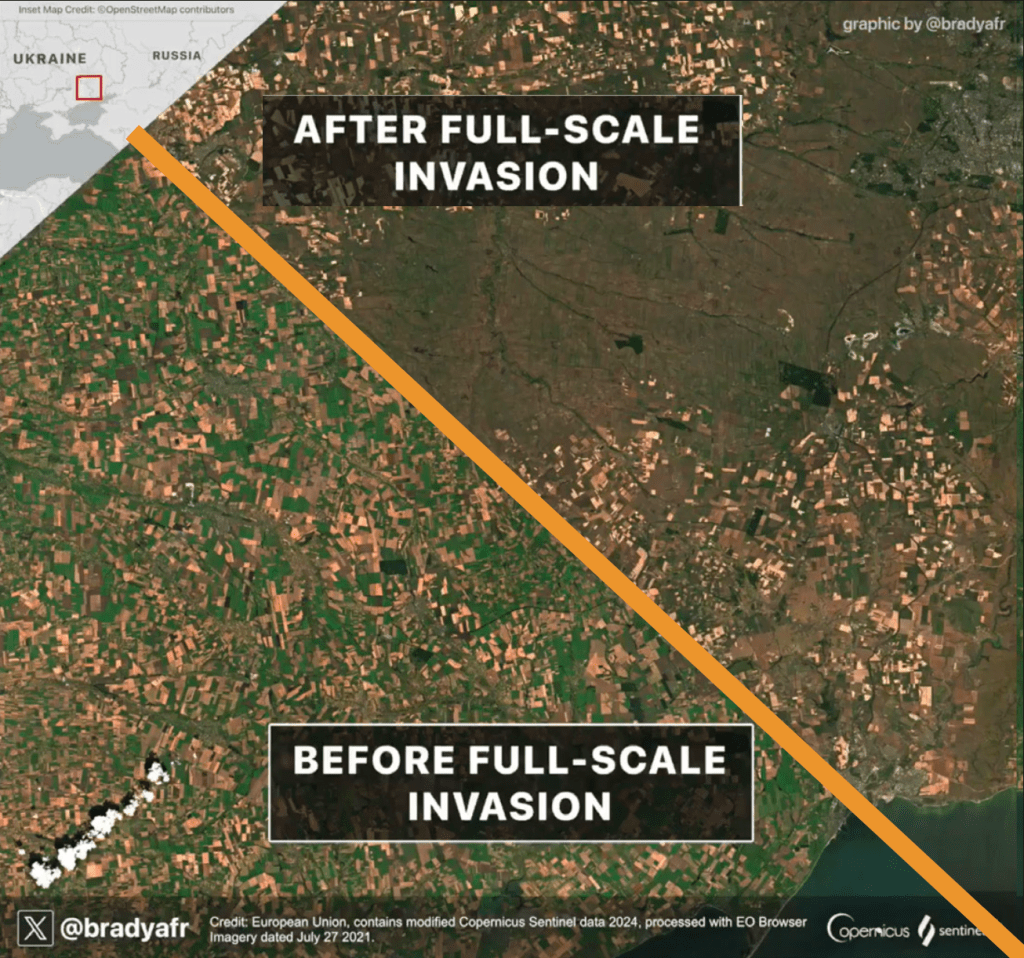

The war in Ukraine is one of the only recent conventional, industrial wars, and in terms of men and materiel. It is by far the largest war of the 21st century, so it is not surprising that it has created major environmental problems. Because the fighting has disrupted agricultural activity, the front lines of the war are even visible from space. A “green belt” of fallow fields, where trees and ground cover have sprung up in the absence of cultivation, can be seen marking the zone of conflict. The effects on the land will almost certainly be long-lasting, as large amounts of unexploded ordnance create hazards even after a war is over. Old land mines and other unexploded munitions injure people and animals in other former conflict zones, such as Bosnia and Cambodia. Also, munitions such as shells and bombs contain heavy metals and environmental toxins that leach into the water supply and soil, which can render crops unsafe to eat and poison aquatic life.

Soil

Ukraine has some of the most fertile soil in the world, called chernozem, which is notable for its very thick layer of humus, or organic matter, and its rich biome, thus making it highly productive and resilient. Largely due to its soil quality, Ukraine is one of the world’s largest grain exporters. Research has shown that traffic from heavy vehicles such as tanks can disrupt soil biomes, and contamination from explosives and metals will likely do the same. Also, crops grown on contaminated soil can take up toxins from the ground, rendering them inedible. Ukraine’s Sokolovsky Institute estimates damage to soils (as of 2023) to be $15 billion. Cleanup and remediation efforts will likely last years after fighting ends, and the UN has declared thousands of acres to be in states of ecological catastrophe.

Wildlife

Ukraine is home to a large diversity of plants and animals, numbering over 70 thousand unique species. However, certain parks in Ukraine are being taken over by Russian forces and, in some cases, habitats of protected species are displaced by Russian military fortifications. The Tuzly Lagoons National Park, which has conducted decades of conservation efforts, has been unable to resume their operations, resulting in a migration failure for migratory fish that support an entire ecosystem of birds. These events demonstrate the cascading effects of the environmental destruction. In 2022, high rates of strandings and deaths of dolphins were observed in the Black Sea, with some appearing to have been killed by naval sonar and pollution from military activity. Additionally, Russian forces have destroyed several dams, releasing large amounts of toxic sediment that flood wildlife habitats and kill large numbers of fish.

The full ecological impacts of the war in Ukraine are likely to remain unknown until years after fighting ends. It is clear, however, that they will be profound.

Middle East

In the last year, the Israel-Hamas war and Israeli invasion of Lebanon have been at the forefront of people’s minds, but conflict has also been ongoing in Syria and Yemen for several years.

Yemen

The conflict in Yemen, mainly between the Houthis and the Republic of Yemen has been a major proxy conflict involving the Gulf states and the West. The destruction of basic infrastructure has had severe humanitarian implications, such as a lack of clean water infrastructure and corollary outbreaks of diseases. Additionally, the Saudi-led blockade precipitated a hunger crisis, placing millions at risk of starvation. As in the Sahel countries, the displacement of millions has intensified deforestation, and ongoing warfare has also led to the destruction of oil facilities. Leaks of oil into soil and drinking water have exacerbated the already severe health crisis, and there is even evidence that cancers have become more prevalent because of war-related pollution.16

Gaza

Gaza has seen some of the most intense environmental destruction. Israeli bombing has destroyed or damaged a majority of structures in Gaza, creating millions of tons of debris, much of which poses environmental hazards. Rubble and debris contain heavy metals, as well as contaminants like asbestos. Like in Ukraine, the leaching of toxins into water and soil will be particularly damaging. Additionally, approximately half of Gazan land was used for agricultural purposes before the war. Today, Israeli armies have destroyed over two-thirds of that area, clearing crops and orchards, often building military sites in place of farmland. The environmental destruction has also impacted Gazan food security—the most intense destruction of cropland was in the north, where famine conditions have also been worst. The UN has estimated that it will take 14 years to clear the rubble from the war, meaning that pollution issues will likely persist.

Ecocide?

Ecocide—the idea that environmental destruction is a crime against humanity—has gained public attention in recent years, with many now viewing it as an offense that should be strongly prosecuted by the international community, even in peacetime. Currently, the Rome Statute prohibits willful environmental destruction in wartime, but due to opposition from the US, it does not apply to peacetime. In the past couple of years, Israel and Russia in particular have faced allegations of ecocide from various international organizations. In a world suffering increasingly from ecological harm, many desire a formal framework to hold the leaders who enable such destruction responsible. A good first step would be to establish international consensus over a definition of ecocide; certain organizations, like Stop Ecocide International, have tried to promulgate definitions already, but an effective definition will require the approval of the international community. Then, work must follow to establish statutes to extradite and prosecute the culprits, perhaps in the International Criminal Court or another recognized international body. These efforts will likely face fierce opposition, but they are absolutely necessary to slow down what seems like an inexorable march toward environmental disaster.

This piece is a reproduction from its original issue in Hemispheres Volume 48 Issue 1. Read more here.