By Julia Rottenberg and Emilia Ferreira

What is the Darién Gap?

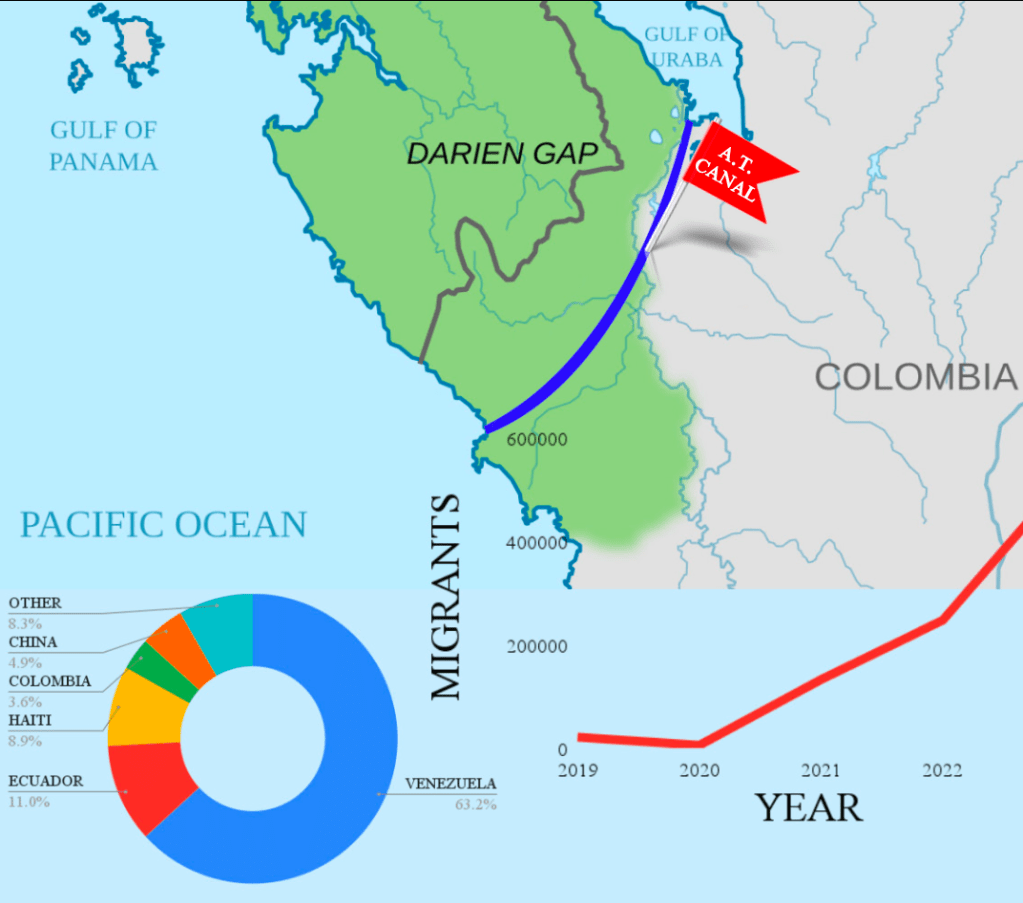

The process of immigrating to the US starts long before migrants arrive at the border. Around 3,000 miles south of the US-Mexico border lies another border: “The Darién Gap.” As the only land-based pathway that connects South and Central America, the 66-mile jungle straddling Panama and Colombia, has been a historically common route for migrants traveling up from South America. Despite its dangers, the route has become drastically popular—over half a million people crossed the Darien Gap in 2023, compared to just around 22,000 in 2019.

Who crosses?

While migrants from Venezuela, Ecuador, and Haiti represent the largest share of those crossing, the Darien Gap is unique in providing a crossroad for migrants from around the world, including those from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Many migrants flee treacherous conditions at home, only to meet similarly precarious situations on the trail. The most represented countries among the Gap’s migrants have all faced internal strife—economic and democratic collapse in Venezuela, political instability in Ecuador, and environmental crises in Haiti—that lead many to seek asylum in the US. About one in five migrants are children, and the lack of medical assistance and frequent injuries along the untamed jungle trail lead many families to separate.

Migrants face not only natural dangers, but also manmade ones. Drug cartels, namely Colombia’s “Gulf Clan,” is a neo-paramilitary group that makes millions smuggling migrants through the Gap. The Gulf Clan exploits both the system and the migrants—while the Clan is responsible for helping many migrants cross the Gap, they are also responsible for much of the abuse, assault, financial cost, and the trafficking the migrants endure and face while crossing.

How did we get here?

The crisis at the Darién Gap is no accident. Through visa laws and requirements, paths of migration, and heavy restrictions, the Darién Gap’s prevalence and precariousness have been manufactured.

The geographical location of the Darién Gap makes regulation difficult. Coordination is required between Panama and Colombia, and there has historically been little interest in tackling a problem of its complexity and magnitude. Additional coordination is required from the US, the main destination country for those embarking on the long journey up Latin America.

US immigration policy has been continuously harsh and unwelcoming towards migrants, most recently with the pandemic-era policy Title 42, which allowed border security and immigration systems to turn away thousands of migrants for COVID control and send them back to a transit country, typically Mexico, or to their country of origin until 2023. While US policy aggressively attempts to stop growth in border crossings, an approach that is likely to heighten under President Trump, migration is unlikely to slow.

Panama has, until recently, taken a relaxed approach to regulating the border while still allowing human rights organizations to aid migrants upon the end of their journey through the Gap and providing humanitarian assistance. However, no forceful approach has been taken in respect to cartel activity.

What now?

Efforts to address the Darién Gap crisis require multi-level collaboration, yet disparate interests and logistical challenges often hinder effectiveness.

Panama’s 2024 presidential election saw President Jose Raul Mulino voted into office, signaling an aggressive turning point in policy concerning the Darién. Mulino has expressed openness to building a route through the Gap controlled by the government—which would require pushing cartels out. However, this strategy would require cooperation with Colombia, the primary entrance point into the Darién and a country that has been inconsistent in its migration policies. It has coordinated cooperative discussions with Panama, yet its attempts to address border security are often complicated by organized crime networks like the Gulf Clan. NGOs have been critical in providing humanitarian aid to migrants along the life-threatening path, but have little agency in mitigating the deeper policy failings that force people into the Darién in the first place. Additionally, a second Trump administration will likely continue a harsh border policy with Mexico and continue to turn away migrants en masse.

The issues that persist with the Darién Gap are substantial on their own, but will never be resolved without comprehensive immigration reform in the U.S., Mexico, and Latin America as a whole, with policies that reflect the reality of the region. The Darién is a part of a larger problem, which is the failings of a multi-country immigration system that cannot be fixed with one policy, action, or initiative. While an American “open border” policy would not remedy the many causes behind the Darién Gap, it is clear that the current discrepancies in border policies between the many countries involved in these migration routes do not benefit the migrants nor the countries’s foreign policy agenda. Without coordinated and comprehensive reforms and an increased investment in safe, legal migration routes, the humanitarian and security crises in the Darién Gap are likely to persist.